I want to tell you about something that happened when I was 26, that I’m only now—at 43—really understanding. And then I want to tell you about what happened recently that made me realize: some things change profoundly, and some things still shake in our bones.

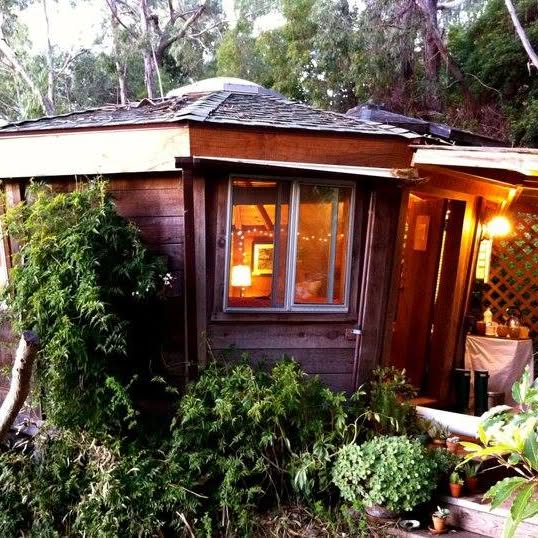

The Yurt at Esalen

I was living and working at Esalen Institute on the Big Sur coast. If you haven’t been there, it’s 27 acres of healing land perched between the mountains and the Pacific, where people have been coming since the 1960s to do deep transformative work. I’d arrived there in what I now understand was early decompensation—when all the strategies that kept my childhood relational trauma manageable were starting to fail. My Peace Corps service in Uzbekistan had initiated this unraveling, and I’d come to Esalen hoping to put myself back together.

In one of our regular community meetings in a yurt, I spoke up against one of the senior leaders. They were making a decision I thought was wrong for our community, and I said so.

I remember absolutely shaking. Feeling completely and utterly terrified. And yet I still did it. Looking back, I’m actually not sure how I did it, but I did it.

Then the senior leader—in front of everyone—shamed me for what I said. Not disagreed with me. Shamed me.

That particular kind of public shaming has a specific quality to it. The heat in your face, the ringing in your ears, the sense of being very far away from your own body while also acutely present. It’s a physiological response that’s hard to describe if you haven’t experienced it.

That experience impacted me a lot, and not positively.

I left the yurt and went straight to the rock wall outside the Esalen Lodge. I cried. I let my body shake and metabolize what had just happened while the Pacific crashed against the cliffs below. A fellow staff member about my age came and sat down next to me. He’d witnessed the whole exchange and came to check on me.

I remember what he said: “I don’t really understand why this is rattling you so much.”

He didn’t say it to be malicious—I want to be really clear about that. He was checking on me, making sure I was okay. He was well-meaning. But for him, he genuinely couldn’t understand why I was so negatively impacted.

When Trauma History Meets Economic Reality

What I can see now but couldn’t articulate then were the multiple variables at play, and how they compounded each other in a very specific way.

First, I was still at the very early stages of my relational trauma recovery. My nervous system had learned early that challenging authority was dangerous. In my family of origin, speaking up against power meant real consequences—withdrawal of love, emotional abandonment, being seen as the problem. So when I spoke up in that meeting, every alarm bell my childhood had installed was going off.

But here’s the crucial part: those alarm bells weren’t wrong.

When you’re economically vulnerable, every professional interaction carries different weight. I was living and working at Esalen. My employment, my housing, my meals—my survival—was tied to staying in good standing with leadership. I had no financial safety net. No family to go home to. No job prospects at that time. The administration literally had control over whether I had a roof over my head and food to eat.

So when I risked the displeasure of leadership to stand up for what I thought was right, and then received that shaming response, I wasn’t just having a trauma response. I was having a trauma response that was also an accurate assessment of real vulnerability.

My catastrophic thought was that I’d compromised my employment, maybe even lost it. That wasn’t actually true—but it wasn’t irrational either. It was my nervous system doing the math: relational trauma history (speaking up = danger) + current economic precarity (job loss = homelessness) = extreme activation.

Here’s what’s important to say: even if I had been further along in my relational trauma recovery, the fact that I didn’t have finances to lean back on—should the worst-case scenario happen and they fired me—that anxiety still would have been intense. The material vulnerability was real.

My well-meaning colleague? He had a loving family who would welcome him home if he got fired. He had some savings. He had other umbrellas to shelter under where I did not. He wasn’t as attached to preserving his employment because he had actual safety nets.

For him, professional disagreement was just disagreement. For me, it was potentially catastrophic.

That literal shaking, that terror—it had both structural and personal roots.