TL;DR –The guilt that rises when you "complain" about your mother in therapy—even as you acknowledge she did her best, bought you school supplies, stayed up when you were sick—reveals an internalized belief that having negative feelings about parents is wrong, a lesson absorbed from family, church, or culture that keeps you trapped in impossible either/or thinking. Your mother wasn't all good or all bad; she was both the woman who gave you life and held you as a baby AND the one who criticized your weight, shamed your emotions, or couldn't provide emotional support when you needed it most. This integrated view—holding both the positive and painful aspects together—isn't betrayal or ingratitude but psychological maturity that allows genuine healing.

Therapy invites you to look backward not for parent-bashing but to see your history more realistically, to feel all your feelings with a compassionate witness, and to integrate experiences that have remained split and unprocessed. The friend whose mother drives cross-country to help with her baby triggers grief not because you're ungrateful but because you're acknowledging what you didn't and won't receive. Releasing judgment about having complex feelings toward your mother allows you to heal what actually happened rather than what you tell yourself should be enough, understanding that adult relationships with parents are privileges to be evaluated, not obligations to be endured.

You’re in your weekly video therapy session with your therapist. You start telling her about what your friend shared with you over the weekend. Your friend told you how her mother is planning to drive cross country to shelter-in-place with her and her baby indefinitely to help them through the Fall and Winter as her maternity leave ends and she returns to work online.

Your friend was elated. Relieved. Gushing about how much she loves her mom and how her mom is like a best friend.

As you recount the news, you feel the tears in your eyes and your throat tightening thinking about complaining about your mother. You tell your therapist, “I just wish… no, never mind.”

“Go on,” your therapist prompts.

“No, it’s just that, I don’t know. I just wish I could count on my mother for the same thing. God, I can’t even imagine what that would feel like! But, ugh, I hate feeling this way. I feel so guilty for complaining about her. I feel guilty about feeling so disappointed with our relationship. Because I mean, she tries her best.”

“Why do I still feel so sad?”

You feel so torn. You feel conflicted.

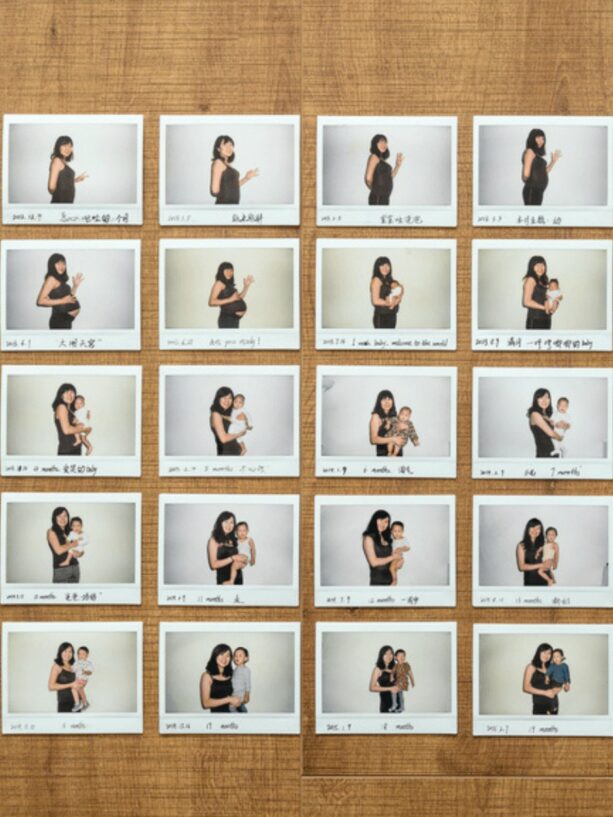

On the one hand, she grew you.

She literally gave you life.

She held you when you were a baby.

And she stayed up late at night with you when you were sick.

Each August in elementary school she bought you new school clothes, a backpack, and three-ring Lisa Frank binders.

You know she loves you in her own way. And you feel guilt complaining about your mother.

And you hold these memories, this knowledge of what she sacrificed, alongside painful memories. Vivid memories.

Memories of being criticized for your weight and stockiness. Jokingly, yes, but still…

Memories, too, where you were shamed for your feelings – “Why are you so angry all the time? What’s wrong with you?”

Of being slapped when you talked back as a teen.

Memories of not having her emotional support when you needed it most and the reality of your brittle, surface-level relationship today as adults.

The kind of relationship that will never look like her driving cross country to help you out in your hour of need.

And you struggle with this.

You struggle to reconcile what you know you “should” be grateful for (and what you are grateful for, in some ways), alongside the pain and anger you hold in your heart towards this one very important person in your life.

If you – like so many people – struggle to reconcile your care and appreciation for your mom alongside your pain and anger with her, if you particularly struggle with this when trying to talk or “complain” about your mother in therapy or in any other context, today’s post is for you.

Therapy is not about parent bashing.

I want to go on the record and say something: therapy is not about parent bashing.

Curious if you come from a relational trauma background?

Take this 5-minute, 25-question quiz to find out — and learn what to do next if you do.

START THE QUIZTherapy and therapists so often get a bad rap for making our clients exhume the past simply for the sake of complaining and “making mom and dad” wrong.

“Shrinks! All they want to do is talk about your childhood!”

I don’t think conflated generalizations like this are ever that helpful.

While therapy absolutely does invite you to turn backward, to look at what was, there is intentionality and clinical reasoning to that.

When we’re able to recall our memories, to make sense of them, and to feel all of our attendant feelings about those memories in the presence of a kind, compassionate witness, we’re able to support our nervous systems and psyches in healing.

So yes, while therapy and therapists will invite our clients to turn backward, to reflect on early life experiences, particularly with our primary caregivers and attachment figures, the goal here is not to “parent bash.”

The idea is to help you see your past, your history, more realistically and more cohesively.

We will invite you to talk about your mother (and father, or mother and mother, or father and father or grandparents – whatever iteration of family raised you) in order so that you can see things more clearly so you can integrate your experiences and get the support you need.

* And, for the intents and purposes of this article, while I use the term mother and birthing language, adoptive mothers and/or any parental or guardian-figure can and should be substituted throughout.

Let’s unpack “guilt” and “complaining.”

But now, let’s unpack and explore what it means to feel guilty and to complain.

Guilt is a signal, an emotional sign that says, “I have done something wrong.”

When we feel guilt rise up in us as we talk about our parents in anything less than positive ways, there’s a clue there for you to pay attention to.

Some part of you thinks you are doing something wrong.

What do you know about this part of you?

What did you learn was okay or not okay when it came to talking about your parents growing up?

Was it okay to ever have negative thoughts about them?

To express your displeasure with them to them?

Please hear me: You are not “bad” or “wrong” for sharing your painful memories about your mom (or parents or anyone) with your therapist.

You may feel like you’re doing something “wrong” or “bad” but that doesn’t mean that you actually are doing something “wrong” or “bad.”

If guilt emerges when you talk about your mom it means that, most likely, that some part of you is conflicted.

You’re likely conflicted because, at some point, whether this lesson came from your parents directly, or from your church or community at large, you learned that speaking about your parents in anything less than positive ways is wrong.

Regardless of when, where, or who you learned this from, it’s simply not the case.

You get to be upset with your parents.

You get to be upset with your mother.

And you get to recall, express, and feel your feelings about painful moments and memories with her.

Doing so does not make you “guilty.”

You have done nothing wrong.

And, moreover, sharing your feelings and memories of the past is not “complaining.”

Sure, technically, complaining is the expression of dissatisfaction or annoyance about something.

But aside from Dictionary definitions, the personal use of complaining in this instance is usually a pejorative, not a neutral definition.

When used as a pejorative, you’re essentially judging yourself for expressing your dissatisfaction or annoyance with your mom.

So let me ask you a question: Could you release that judgment?

Could you allow yourself to simply have your experience talking about her?

What would it feel like to allow yourself permission and space to share your experiences and memories about your mother without an added layer of judgment and guilt?

What would that feel like?

It’s not either/or, it’s both/and.

So, now that we’ve established that there is a clinical reason to reflect on your memories of your mother and that doing so does not make you wrong or bad, it’s important to understand that your experience with your mom was not either/or.

Your experience with your mother was both/and.

What do I mean by this?

Your mom was not fully bad. Nor was she fully perfect.

You may have many memories of her when she showed up as a good, loving, caring mother. A good enough mother.

And you may have memories, too, where she failed you. Possibly egregiously due to her own limitations and circumstances.

When we can hold both of these realities together – the mother who was good enough and the mother you sometimes (or often) failed you – we arrive at a more integrated view of your mother.

We arrive at a more moderate, realistic view of our mothers and of reality.

You move away from idealizing and demonizing her – seeing her as only good or only bad – and instead towards integration.

In psychotherapeutic terms, when we fail to hold this integrative view, when we find ourselves thinking only in black and white, or all-or-nothing thinking, we’re engaging in a psychological defense known as splitting.

Splitting is an inability in someone’s thinking to hold the dichotomy of both the positive and negative aspects of someone else (or ourselves or the world) into a cohesive whole.

If you do have this tendency to “split” in your thinking, please know you probably come by it very honestly and that there’s room for this kind of thinking to grow and to change.

But, for that change to happen, you’ll need to practice doing precisely what feels uncomfortable: challenging yourself to see and hold and accept both the positive and negative aspects of another person.

Such as with your mother.

Why holding both views matter.

Now, it may go without saying but the ability to hold both positive and negative aspects of another person – such as with your mother – is a healthy, positive thing.

First, it allows you to actually have your feelings if you’ve been resisting acknowledging the painful memories or experiences you have with someone.

When we can name that, even though we love someone, they caused and are still causing us pain, it opens up the possibility for us to feel more fully, to make more sense of our experiences, to seek out the right supports, and to decide more clearly what, if anything, we may need or want to do in that relationship.

As the old therapy saying goes: “We cannot heal what we cannot feel.”

Allow yourself the opportunity to heal by acknowledging your full spectrum of feelings about your mother.

Second, when we can hold both views – both the painful and the positive aspects of our mothers – it can help you grow more accustomed to holding integrated views of others, and with yourself.

And when we can do this – hold more integrated views of others and ourselves – we deepen our capacity for more stability and flexibility in our relationship patterns.

We give others and ourselves permission to be imperfect, to fail, to have ruptures with us, and for there to be space for this imperfection and human reality in our relationships.

Now, a caveat.

Just because your mother was imperfect and just because it’s good to hold integrated views of others, does not mean that I’m suggesting that you love her, stay in a relationship, or resume a relationship with her if that contradicts your own intuition and your boundaries.

I’ve said this before, but I’ll say it again: having a relationship with an adult child is a privilege, not a right.

If it doesn’t feel safe, and healthy, and supportive for you to be in touch with your mother, then you don’t have to.

You’re always in control of your boundaries and who you let into your life as an adult.

This, I think, is one of the greatest things about being an adult: having a choice about who gets to enter your life. It’s something most of us didn’t have as children.

So even as we work to hold the dichotomy of both aspects of your mother, even as we work to undo the “guilt” you feel for talking about her in anything less than a positive light, please know you don’t have to be in a relationship with her if that doesn’t support you.

Processing Mother Ambivalence Through Integration-Focused Therapy

When you struggle to tell your therapist about your mother’s failures, prefacing every criticism with “but she tried her best,” suffocating under guilt for having any negative feelings about the woman who gave you life, you’re wrestling with what makes mother wounds uniquely complex—the impossibility of reconciling feeling guilty about complaining about your mother with the legitimate pain she caused, whether intentionally or through her own limitations.

Your trauma-informed therapist understands that mother ambivalence creates particular suffering because society, religion, and family systems often demand pure gratitude toward mothers while denying the reality of maternal harm. They recognize how “splitting”—seeing mother as all-good or all-bad—protects you from the overwhelming grief of accepting that the person who should have loved you best also failed you significantly. The guilt isn’t about actual wrongdoing but about breaking powerful taboos against acknowledging maternal imperfection.

The therapeutic work involves developing capacity for integration—holding both truths simultaneously without splitting. Your therapist helps you practice: “My mother bought me school supplies AND criticized my body.” “She stayed up when I was sick AND couldn’t tolerate my emotions.” “She loved me in her limited way AND that way wasn’t enough for what I needed.” Each both/and statement challenges the either/or thinking that keeps you stuck between inappropriate guilt and unexpressed rage.

Together, you explore what you learned about criticizing your mother—perhaps that it meant you were ungrateful, bad, or would lose her love entirely. Your therapist helps you understand that sharing painful memories isn’t complaining or betrayal but necessary truth-telling for integration. They validate that you can appreciate what your mother did provide while grieving what she couldn’t, that understanding her limitations doesn’t obligate you to accept ongoing harm.

Most importantly, therapy provides the relational safety to feel the full spectrum of your mother feelings—the love, disappointment, rage, grief, and longing—without judgment or rushing toward forgiveness. Your therapist models what your mother perhaps couldn’t: the ability to hold complexity, tolerate difficult emotions, and see you as whole even when you’re expressing “negative” feelings that were never allowed before.

Wrapping this up.

As I wrap up this essay I want to reiterate one more time: you get to have your feelings and thoughts about your mother.

All of them.

She was not perfect and she may have failed you and, in her own way, she likely tried to do her best (though sometimes people’s “best” is, frankly, awful).

No matter the unique context of your own childhood and your present adulthood, please allow it to be okay for you to recall and express your full spectrum of memories about your mother.

Now, I’d love to hear from you in the comments:

What’s one way that holding both the positive and negative aspects of your own mother has supported you and your own healing as an adult?

Please feel free to share your experience in the comments below so our community of readers can benefit from your wisdom.

Here’s to healing relational trauma and creating thriving lives on solid foundations.

Warmly,

Annie